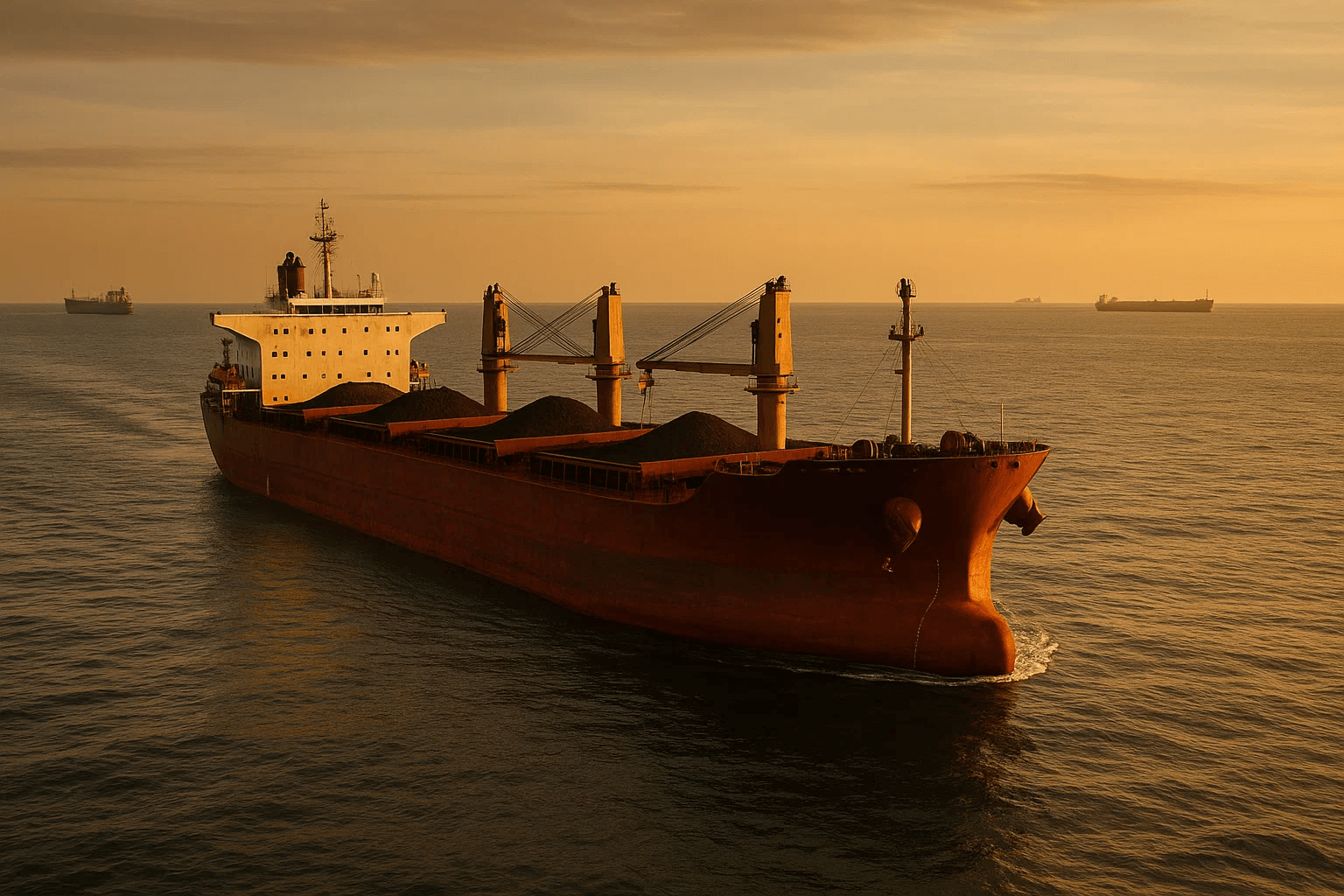

On November 9, 2025, Guinea reached a long-awaited milestone as the first iron ore loading operation linked to the Simandou Project began at Morebaya Port. The event marked the symbolic start of what could become one of the most important new sources of seaborne iron ore supply in decades. The operation involved the vessel MV Winning Youth, loaded offshore under the supervision of officials from several Guinean authorities, including Customs, Police, and the Navy, along with representatives from the Winning Consortium Simandou (WCS) and Rio Tinto. Their presence underscored the national significance of this achievement, described as “a bridge to development” by project leaders.

The Simandou deposit, located in southeastern Guinea, is often called the “sleeping giant” of the global iron ore industry. It is one of the world’s largest and highest-grade undeveloped iron ore resources, with an average grade around 65% Fe. After years of delays and challenges—ranging from political instability to the sheer difficulty of building a 600-kilometer railway through rugged terrain—the project is finally moving toward large-scale exports. Around two million tonnes of high-grade ore are ready at the mine site for export, and production is expected to ramp up steadily toward 120 million tonnes per year by 2028.

For the global dry bulk market, and especially for capesize vessels, the Simandou project carries major implications. Iron ore is the lifeblood of the capesize segment, which relies on long-haul cargoes moving between major producers and steelmaking centers. Until now, the seaborne iron ore trade has been dominated by flows from Australia and Brazil to Asia, particularly China. With Simandou entering the market, a new West African export hub is emerging, potentially adding 8 to 9 percent to global seaborne supply once fully operational.

This new trade flow will likely reshape global shipping routes. A capesize loading in Guinea will typically head east via the Cape of Good Hope to reach Chinese or Southeast Asian ports — a long voyage that adds ton-mile demand, which is positive for the freight market. The emergence of a new loading port on the Atlantic coast also creates new logistical opportunities, not only for shipowners but also for regional economies that could benefit from related infrastructure and service industries.

For shipping, the immediate impact of Simandou’s first shipment is largely symbolic, but it signals the beginning of real tonnage movement from a project long considered “too big to happen.” Over time, as output grows, the new cargoes could boost demand for large bulk carriers, tightening the balance in the capesize segment. However, if Simandou’s high-grade ore displaces lower-grade supply from other regions rather than simply adding to global demand, the overall impact on freight rates may be more nuanced.

Still, from a maritime economics perspective, Simandou represents a structural change in iron ore trade dynamics. It diversifies supply, lengthens voyage distances, and brings a new player into a market traditionally dominated by two export giants. Morebaya Port itself, now equipped to handle large ocean-going bulk carriers, stands as a physical symbol of Guinea’s entry into the front line of global commodity logistics.

In the broader picture, the project is not just about mining. It is a story of infrastructure, investment, and connectivity — of railways, ports, and the ships that will carry Simandou’s ore across the oceans. For the dry bulk sector, especially the capesize fleet, the first loading operation on November 9, 2025, may well be remembered as the start of a new and transformative trade route in global shipping history.